Photoscreening 101: Is the world blurry to your young child?

Parents and physicians assume that if a child has blurry vision, they’ll recognize it. The child will complain of vision problems. Yet, the truth is that young children don't know if how they see the world is how others see it. Children needing vision correction rarely complain of symptoms. About 70% of early childhood vision screening in the US takes place in a pediatrician or primary care doctor's office. Traditionally, this involves a physical examination and a visual acuity test using wall charts. Visual acuity charts have much value in the clinical setting. They're easy to use, but they have limitations for young children.

The test can take up to five minutes, which is challenging for the youngest patients. It's generally not possible to screen children under three years old with a visual acuity chart. Plus, there are often variations in technique due to visit time pressures and staff turnover.

Check kids' vision before they can read an eye chart

These limitations led several US groups to recommend instrument-based vision screening. The American Academy of Pediatrics and the US Preventive Service Task Force updated their vision screening policies about six years ago. They recommend instrument-based screening, when available, as early as 12 months and annually at well-child visits. These policy updates and a growing body of evidence steered others, including Bright Futures, to adopt similar recommendations.

The primary objective of early childhood vision screening and instrument-based vision screening is to detect the presence of conditions that are risk factors for amblyopia if not treated early.

Those risk factors include:

- Myopia (nearsightedness)

- Hyperopia (farsightedness)

- Anisometropia (asymmetrical refraction)

- Astigmatism (an imperfection in eye curvature)

- Strabismus (eye misalignment)

Photoscreening is the most common type of instrument-based vision screening. The devices estimate the refraction in each eye to determine if there's a risk that warrants a referral for a comprehensive evaluation. At under a minute, photoscreening is faster than visual acuity chart testing. And it takes place at a shorter distance, making it easier to accomplish in an exam room.

Vision screening is as easy as taking a photo

Photoscreeners use a flash of light (like a camera flash) and analyze that light as it travels through the cornea and lens to the retina and then reflects off the retina back through the lens and cornea to the camera. Focusing the eye at the source creates a point on the retina. The reflection of the light looks different in a child with a refractive error in the eye or other refractive changes versus a child without a refractive error.

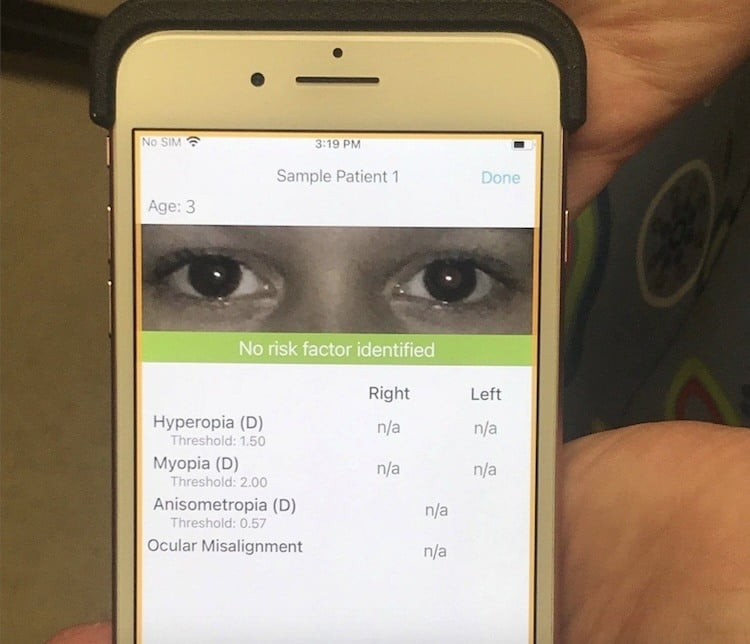

The GoCheck Kids screener is built around a smartphone--something children are used to people using to take their photo. Other photo screeners are medical devices built like medical cameras specifically for photo screening. All photoscreeners use either visible or near-infrared light.

The device’s software evaluates the pattern of the reflections of the light from the image and, based on those measurements, estimates the score for different risk factors. The pediatrician uses that information to determine if the child should be referred for a comprehensive evaluation.

Screening tools aren’t diagnostic tools

As pediatricians, we know how common false positives and negatives are for screening tests. Instrument-based vision screening is no different. Photoscreeners available in the United States have all been shown to have a similar range of performance in terms of sensitivity and specificity. Those numbers are commonly 70%, 80%, and occasionally 90%.

If a child gets a positive result on an instrument-based screening, the recommendation is a comprehensive eye exam by an eye care specialist. The evaluation looks for evidence of vision risk factors. A pediatric ophthalmologist, a general ophthalmologist, a pediatric optometrist, or a general optometrist are all qualified to evaluate a child through a cycloplegic refraction exam.

It's not uncommon for a child to have an eye exam after a photoscreening picks up hyperopia, for example, and the diagnosis is stigmatism. The important thing is that there was evidence of a risk factor, and a comprehensive eye exam will determine it more specifically.

As part of a well-child visit, in addition to a photoscreening, you’ll ask about family history, personal history, and conditions that might cause vision trouble and do a physical exam for evidence of vision disorders. By themselves, each of these items isn’t perfect (or comprehensive), but together they can identify children at the highest risk before they can communicate that something's wrong.

Deciding if a photoscreener is right for your practice

In the US, several screeners are commercially available for pediatricians. All of them have been well studied, and they have similar performance for sensitivity and specificity. Prevent Blindness publishes a list of approved screening devices. While pediatricians may not be familiar with this group, they offer helpful materials on vision screening programs.

When it comes down to deciding on the instrument-based screener, I’ve found pediatricians weigh whether it:

- Integrates with their electronic health record

- Is easy to use

- Has the best return on investment for the practice

The good news is that there are three good screeners in the US marketplace. Since they’re clinically similar, using any one is better than not doing instrument-based screening at all. It makes a difference to catch these kids early. If they get earlier treatment, their outcomes are better. And they have a better start in preschool, kindergarten, and grade school, which can affect the trajectory of their lives.